When the Music's Over

History #1 - My Summer of Love and an unconventional friendship with Jim Morrison

NOTE: This is a creative non-fiction personal essay based on an interview with an old friend of The Doors frontman.

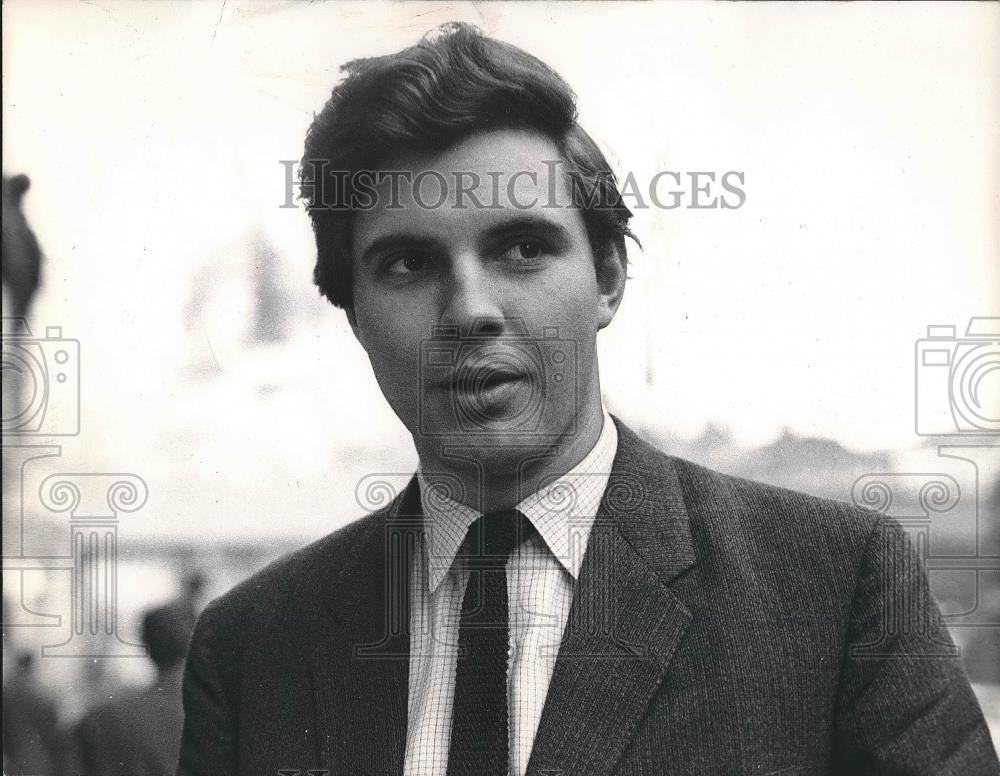

In the early months of 1967, I was based in Saigon as a war correspondent for a British newspaper. I was 24 years old and making quite a name for myself as a risk-taker. I’ll admit that I loved every moment of my reporting on the chaos, though I can’t deny I was frightened by some of the things I saw. The tide was turning against the American troops in favor of the extraordinary resilience of the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong. The conflict had escalated into carnage.

By June of that year, it was time to move on. After an eighteen-hour military flight from Vietnam to the U.S. Air Force base in Oakland, California, I traveled to a hotel in San Francisco and crashed into bed. I was awoken by a group of men smashing down my door with axes. After multiple phone calls attempting to rouse me, they thought I was dead. Slightly embarrassed, I assured the hotel manager I was perfectly fine, just exhausted. We struck up a conversation about my work.

“There’s a story in today’s paper that’s been going on for some time about the hippies. They’ve taken over Haight-Ashbury,” he told me.

“What are hippies and where’s this hate place?” I asked, bemused.

“Drugtakers. Musicians. Artists. They’re shaking up the city. Every weekend, tens of thousands of them arrive from all over the United States and swarm The Haight—where Haight Street crosses Ashbury Street. It’s become a counterculture movement.”

This sounded like a story the paper would be interested in. “I want to meet some of these folks. Will you take me?”

He warned that it was not a place for respectable people, but after coming from the front lines of Vietnam and being shot at, nothing could deter me.

Arriving in a bohemian ghetto of love teeming with flowers, multi-colored shirts and kaftans, the hotel manager and I made an incongruous pair, he in his Hilton uniform and me in a jacket and tie. I noticed hippies wearing badges with messages such as: ‘Take A Trip – Fly LSD.’

Subversive energies surged the incense and marijuana-scented streets as record players spun on repeat, ‘If you’re going to San Francisco, be sure to wear some flowers in your hair...’ These energies were soon to become protests from a generation that abhorred the Establishment and the Vietnam War.

Before my eyes, I was seeing quite a story—of opposition and rebellion and community. I bid my guide farewell, deciding to hang around and explore this unconventional utopia where everything was ‘groovy.’

One of the first people I met was a bearded sage named Allen Ginsberg. It was Ginsberg who coined the term ‘Flower Power’ as a symbolic action of passive resistance to Vietnam. He immediately befriended me upon hearing that I was fresh off the battlefields and bursting with eyewitness stories.

Ginsberg was thrilled to hear that I knew The Beatles—I had met the Fab Four in Oxford—and my arrival on the Haight-Ashbury scene coincided with the release of their sensational eighth album, Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band—on heavy rotation in all the cafes, ashrams, and radio stations. My timing could not have been better. As an Englishman who could ‘tell it like it was’ about Vietnam—and knew The Beatles to boot—I was quickly ensconced into Ginsberg’s circle of poets, musicians, and anti-war protestors.

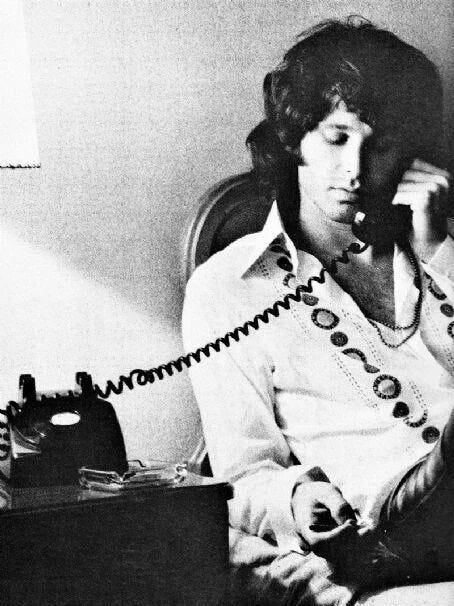

For the next couple of weeks, I would congregate in that rundown neighborhood of San Francisco as one of Ginsberg’s posse, which included Jim Morrison, the frontman of The Doors, and Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKernan of the Grateful Dead. As a temporary insider to this starry scene, my war stories of Vietnam ignited passionate conversations. They were hanging onto my every word, though I’m sure my British accent made me that much more intriguing.

One day, as I sat in an ashram amidst a haze of marijuana with my new best friends, the bulky, barrel-chested colossus that was Pigpen looked at me and said, “Would you like to come to Monterey with us this weekend?”

The Monterey Pop Festival—spearheaded by John Philips of The Mamas and The Papas, record producer Lou Adler and the publicist for The Beatles, Derek Taylor—had been organized in less than seven weeks. The objective of this visionary team was to put on a groundbreaking event that would validate rock music as part of mainstream culture.

Leaving LA with my sleeping bag in tow, I was in great company. For the first six hours of that long and memorable road trip, I accompanied Pigpen and the rest of the Grateful Dead in their van where they started their performance early with an impromptu jam. Together we turned on, tuned in and dropped out to their magnificent music and the electrifying charisma of Jerry Garcia, a singular sensation.

We made a few stops on Highway One to smoke joints and look at the ocean. Jim was in convoy, coming along to Monterey as a spectator. At one point, he stepped out of his Mustang and turned to me, “Hey man, can you come in our car now and drive? You’re probably the least high of any of us.”

Blasting from his cassette player was Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band. Jim was trying to analyze the lyrics of A Day in the Life and Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, asking me to give him the meaning as if I were an interpreter of The Beatles. Barreling down the scenic North Californian coast, I tapped the steering wheel to the beat while he grinned at me from the passenger seat and sang along: “I get high with a little help from my friends.”

It was a wild and happy time.

There was much anticipation and excitement in the fairground of Monterey. The performers were appearing for free and the tickets were a nominal $3, with all revenue going to charity. The growing hype had attracted so many people, the authorities were overwhelmed. Derek Taylor hurled me into a panic-stricken meeting with the local police chief and Minnie Coyle, the Mayor of Monterey. I attempted to pacify them by addressing Minnie as “Madam Mayor,” explaining that I had once been a Special Constable helping direct traffic at the Aldeburgh Festival in England and there had been no trouble at all.

I struggled to keep a straight face as John Philips earnestly assured them: “And I can promise you there will be absolutely no drugs.”

The unscheduled arrival of a clique of flower children capped the meeting as they festooned the police and councilors’ necks with garlands of red and white roses chanting, “Love, Joy and Peace!” Madam Mayor turned to me and beamed, “Amen to that!”

It’s funny to think that my bearing witness firsthand to the ferocity of war from the frontlines of Vietnam would grant me a front-row seat—or rather, a backstage pass—to a seminal event in music history. I was free to roam all areas, but I spent much of those three days on the grass, basking in the Californian sunshine as I lived and listened to The Mamas And The Papas California Dreamin’ in real-time. I was spellbound by Simon and Garfunkel’s The Sound of Silence and my body tingled to Joni Mitchell’s Ladies of The Canyon.

The spectacular lineup of performers also included Janis Joplin, Otis Redding, and Jefferson Airplane. Two of the sets ended in destruction when Pete Townsend of The Who demolished the stage, drums and amplifiers with his guitar. This was an act of violence never seen before on the American music scene and was entirely at odds with the peace and love atmosphere. Jimi Hendrix, still relatively unknown in America, sought to outdo The Who. He ended his set in pyrotechnic anarchy by pouring lighter fluid over his guitar, setting it ablaze, and whipping the crowds into a frenzy. A rock star was born.

‘Acid rock’ and ‘acid politics’ seemed to be the leading themes of the event as LSD parties took place on the grassy areas of the fairground. The lead singer of The Byrds announced from the stage, “One of the most important statements in history has been made by Paul McCartney: If the politicians would take LSD, there wouldn’t be any more war.”

I filed a series of dispatches on Monterey. My articles were causing quite a stir in England as I was tapping into the protest movement that was sweeping Sixties America, the axis of change in the counterculture, and the rebellious rise of the new generation.

Jim and I continued to see each other regularly back in LA. We would meet up for breakfast on Venice Beach, and though we couldn’t have been more different, we became friends. He was a revolutionary thinker and wanted to pick my brains on all sorts of subjects, particularly Vietnam. He grilled me on subjects he’d only heard about second-hand, such as napalm raids, firefights, and ‘harassment and interdiction’ artillery bombardments. His eyes widened as I recounted my exhilaration of being shot at and missed. One thing we had in common, besides our youth, was a feeling of immortality, and our proclivity to dance with death.

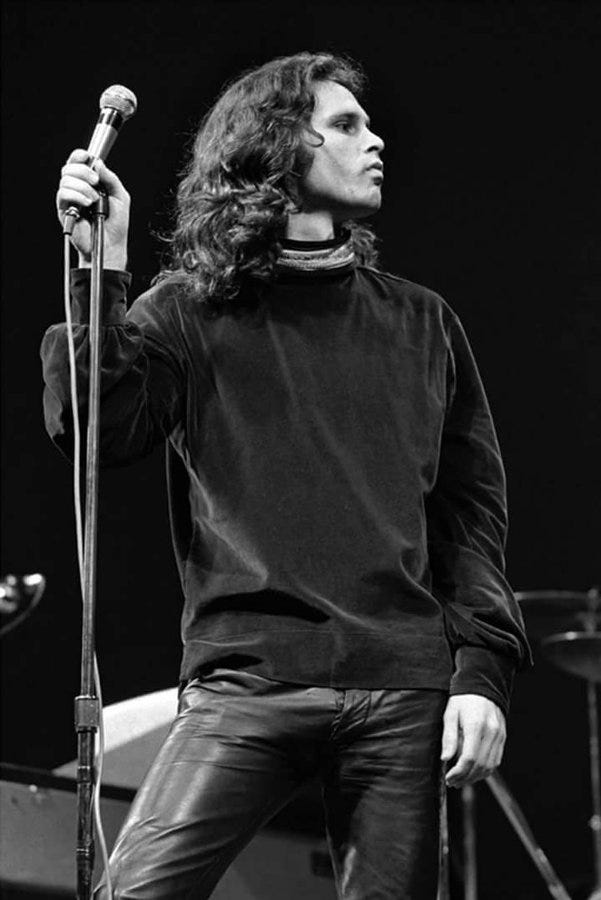

Jim invited me to see him perform the following year at the Fillmore East in New York. I will never forget his incendiary performance of Light My Fire. The chorus went on for about 40 minutes, the audience was enraptured. Most of us were high as kites, dancing the night away in a kingdom of nirvana.

That was the last time I saw my friend. Jim’s light was too hot and bright for this world. I suppose The End was inevitable, but it came far too soon. He was like a comet, a cosmic rock star that crashed and burned. His music will live on forever.

Great view into an important moment in music and history.

You are such a talented writer! Love reading your pieces! Always been a huge JM fan but lost touch w thinking about him so thank you for the revival. Keep up the amazing work!