War Heroes

History #2: Two RAF fighter pilots of WW2 - a Canadian conformist and a rebel from New Zealand - my grandfathers

As a child, my imagination ran wild with various identities that could solve the mystery of my nameless, faceless father. One recurring daydream was a romantic war hero.

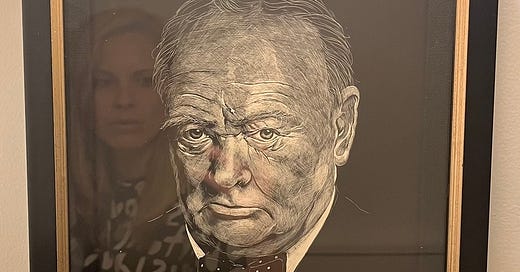

As a teenager, I became convinced my father was Winston Churchill. Not Sir Winston Churchill, but close enough: his grandson, whose father, Randolph, had named his only son after his father. The Conservative MP grandson of Sir Winston Churchill, most likely crushed by the weight of carrying the same name as his legendary war leader grandfather, once had a scandalous, years-long affair with my mother. I learned about this with considerable embarrassment through a newspaper at boarding school. Notwithstanding, so convinced that Churchill Jr. was my father, I wrote him a letter asking him outright and sent it off to the House of Commons.

As an adult, through a series of astonishing coincidences, I began to piece together the complex jigsaw of my identity. My childhood imaginings of heroism were powerful enough to manifest into reality: a DNA test confirmed that I shared blood with a few war heroes, two of whom were amongst the brave group of RAF pilots known as “The Few” who defended Britain against the German Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain during the summer of 1940, a historic victory and critical turning point of WW2.

I did not get to meet these two remarkable men, but as the fathers of my parents, they are part of me, the makers of my makers. Their paths may only have crossed in the skies, but during times of great personal difficulty in my own life, I have summoned their warrior spirits to empower me with the strength and courage for which they are remembered.

This is the story of my war hero grandfathers.

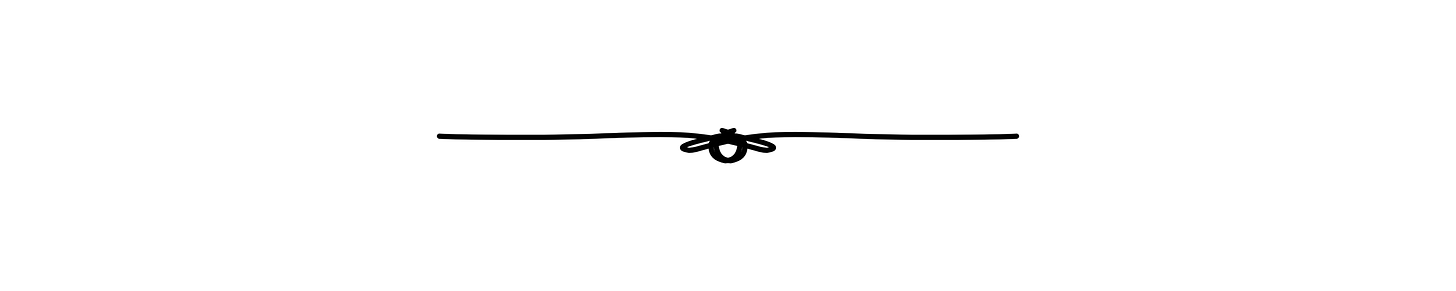

Sir William Traven Aitken (1905 - 1964)

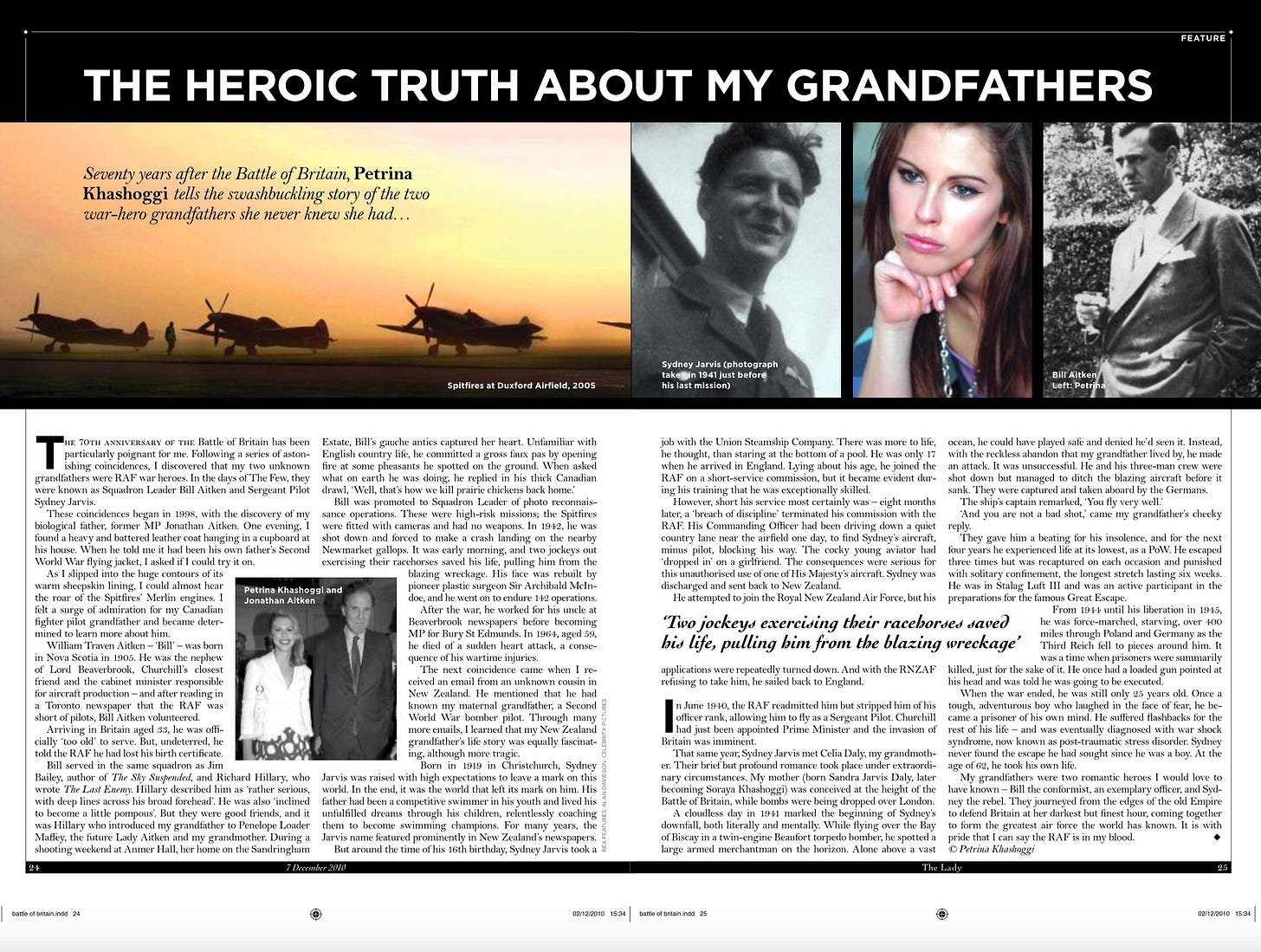

My first and only contact with Bill Aitken was through his jacket. Not a suave smoking jacket like the one implied in this newspaper clipping, but his Second World War flying jacket.

One winter evening in 1998, my father heaved a battered leather garment out of a coat cupboard at his London home. We had only recently become acquainted, and though I barely knew him, I hung onto his every word. Here was the man I had been dreaming about for eighteen years, and this was my first family history lesson. His voice potent with pride, he told me the jacket had belonged to his father, adding, “Why don’t you try it on?”

Wearing clothes was my job — I was a fashion model — but this tremendous relic was by far the most meaningful sartorial item I had ever been asked to try on. As I slipped into the huge contours of its warm sheepskin lining, I could almost hear the Spitfires’ Merlin engines roar. I met my father’s smiling eyes with a surge of admiration for my Canadian fighter pilot grandfather, eager to hear all about him.

Bill Aitken was born in Nova Scotia in 1905 and later settled in Toronto. Frustrated by his office job in the city and lacking romance, he had a burning desire to see the world and find true love.

On weekends, to escape his humdrum life, Bill volunteered as a territorial army officer in the Toronto Scottish Regiment. He was trained as a reconnaissance pilot, acquiring specialist skills to take aerial photographs of targets on the ground. This skill soon became a great passion that would take him to England to serve in the Battle of Britain, one of the most celebrated moments of the Second World War.

In 1938, Bill read in a Toronto newspaper that England and Germany were on the brink of war and the RAF was in desperate need of pilots. He wrote to the Air Ministry in London and informed them he was a fully trained reconnaissance pilot willing to volunteer.

Bill’s Uncle Max, the Canadian media magnate Lord Beaverbrook, was already a British resident and one of only three people — alongside his close friend, Winston Churchill — to sit in Cabinet during both World Wars (serving as Minister of Information in WW1 and Minister of Aircraft Production and Supply in WW2.)

Upon arriving in England, Bill reported to the Air Ministry and produced his qualifications. The RAF was so impressed by his experience and so keen to have him that they told him to burn his birth certificate. At 33, he was too old to serve, but these were desperate times. His papers were adjusted to give him the new age of 26.

At an isolated base in Norfolk, Bill was now living his dream as a flight lieutenant in training, a far cry from his dull office job in Toronto. All that was missing from his life was love, and he had little hope of finding it in the wilderness. He became friends with a young British administrative officer at the same base named Alan Loader Maffey.

Alan’s father was the distinguished diplomat Sir John Maffey (later Lord Rugby), Head of the Foreign Office, and a highly decorated crown servant. He had been Private Secretary to the Viceroy of India, Governor of the Northwest Frontier Province, Governor of Punjab, and Governor General of the Sudan. Later, at Churchill’s request, he became representative to Ireland during WW2.

Alan took Bill, the lonely Canadian with wings (but no social life) under his own proverbial wing and invited him to spend the weekend with “my people.” Bill knew nothing about the British class system or English country life. Socially awkward and unprepared, he showed up at Anmer Hall — Alan’s family home on the Sandringham estate (now home to the Prince and Princess of Wales, a wedding gift from Queen Elizabeth II) — wearing his RAF uniform. He had brought nothing else to wear but his pajamas.

Alan’s sister, a vivacious young girl named Penelope, so pretty and popular she had been made ‘Debutante of the Year’, was also at home for the weekend. Penelope had a long line of suitors courting her, but it was the gauche weekend guest with the thick Canadian drawl who caught her attention. Bill’s unintentional comedic antics made her double over with laughter on the golf course and later, at the dinner table.

Bill was invited to stay with Alan’s family at Anmer Hall again, this time for a shooting weekend. He managed to wear appropriate attire but committed a gross faux pas by opening fire at some pheasants on the ground, explaining himself with: “Well, that’s how we kill prairie chickens back home.”

Alan’s hilarious and attractive new friend Bill, a real-life Charlie Chaplin, had captured Penelope’s heart. Within six months, they were married.

In 1939, the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. By May of the following year, Winston Churchill was elected Prime Minister, and Bill’s uncle, Lord Beaverbrook, was appointed Minister of Aircraft Production. RAF Fighter Command was desperately short of trained pilots and aircraft. Under Beaverbrook’s leadership, fighter and bomber production increased so much that Churchill declared:

At the same time, the splendid, nay, astounding increase in the output and repair of British aircraft and engines which Lord Beaverbrook has achieved by a genius of organisation and drive, which looks like magic, has given us overflowing reserves of every type of aircraft, and an ever-mounting stream of production both in quantity and quality.

The Battle of Britain, fought solely by air forces, took place between July and October 1940, during which Britain successfully defended large-scale attacks by the stronger Luftwaffe.

The gratitude of every home in our Island, in our Empire, and indeed throughout the world, except in the abodes of the guilty, goes out to the British airmen who, undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning the tide of the world war by their prowess and by their devotion. Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.

- Winston Churchill on “The Few.”

Bill was an exemplary officer who served in the same squadron as Jim Bailey, author of The Sky Suspended, and Richard Hillary, who wrote The Last Enemy, one of the classic eyewitness accounts of WW2. Perceived a starkly different man at work to the comedian at Anmer Hall, Hillary described Aitken as “rather serious, with deep lines across his broad forehead… inclined to become a little pompous.”

What Bill might have lacked in social skills amongst the British Upper Class, he more than made up for in service to the country. Promoted to Squadron Leader of photo-reconnaissance operations, he undertook high-risk missions; the Spitfires were fitted with cameras and had no weapons.

Early one morning in 1944, Bill was shot down and forced to make a crash landing on the nearby Newmarket gallops. Two jockeys out exercising their racehorses saved his life, pulling him from the blazing wreckage. Badly injured, his face was rebuilt by pioneer plastic surgeon Sir Archibald McIndoe, and he went on to endure 142 operations. Meanwhile, his wife Penelope, a wartime volunteer helping evacuate German children to Ireland, had given birth to their son and daughter.

After the war, Bill worked for his Uncle Max at Beaverbrook newspapers before becoming MP for Bury St Edmunds. In 1963, he was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the Queen’s Birthday Honours. A year later, aged just 59, he succumbed to the consequences of his wartime injuries and died of a sudden heart attack.

Sydney Jarvis (1919 - 1981)

Ten years after learning about my paternal grandfather and his active role in the Second World War, I received an email from an unknown cousin in New Zealand who had known my maternal grandfather, an RAF bomber pilot who had also fought in the Battle of Britain. My mother never knew her father, so she never spoke of him.

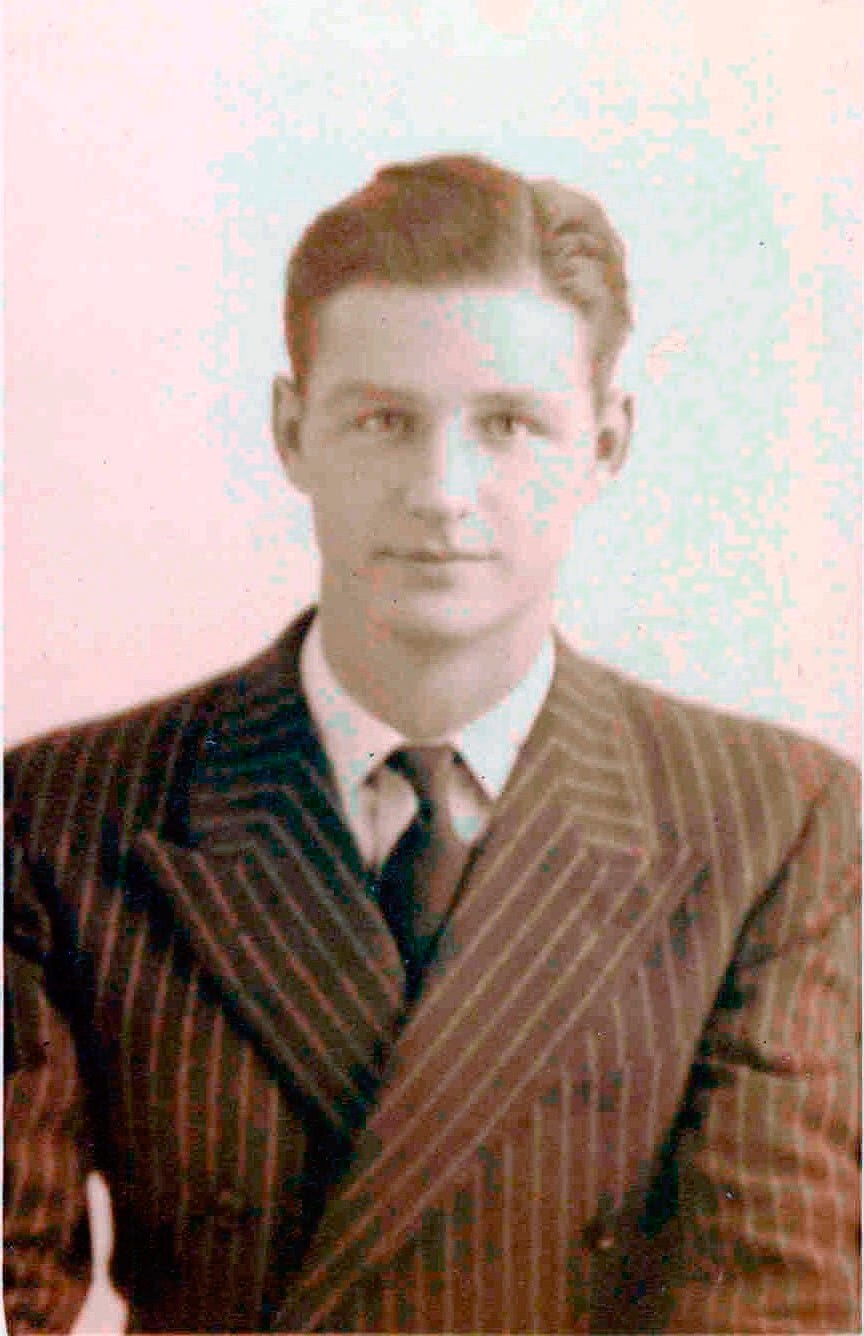

Through continued email communications with my long-lost cousin, I learned about Sergeant Pilot Sydney Jarvis, my other war hero grandfather.

Born in 1919 in Christchurch, Sydney Jarvis was raised with high expectations to leave a mark on this world. In the end, it was the world that left its mark on him.

Sydney’s father had been a competitive swimmer in his youth and lived his unfulfilled dreams through his children, relentlessly coaching them to become swimming champions. For many years, the Jarvis name featured prominently in New Zealand’s newspapers.

Around the time of his sixteenth birthday, Sydney took a job with the Union Steamship Company. He dreamed of wings and felt there was more to life than staring at the bottom of a pool.

Sydney arrived in England in 1937 and lied about his age to join the RAF on a short-service commission. During his training, it became clear that he was exceptionally skilled, but eight months later, a breach of discipline terminated his commission with the RAF. Short his service most certainly was.

His Commanding Officer had been driving down a quiet country lane near the airfield one day to find Sydney’s aircraft (minus a pilot) blocking his way. The audacious young aviator had ‘dropped in’ on a girlfriend. The consequences for this unauthorized use of one of His Majesty’s aircraft were grave. Sydney was discharged from the RAF and sent back to New Zealand. He attempted to join the Royal New Zealand Air Force, but his applications were repeatedly turned down. Undeterred, he sailed back to England.

In June 1940, the RAF readmitted him but stripped him of his officer rank, allowing him to fly as a Sergeant Pilot. Churchill had just become Prime Minister, and the invasion of Britain was imminent.

That same year, Sydney met Celia Daly, a young girl working at an RAF parachute factory in Hatfield. Their brief romance occurred during the height of the Battle of Britain when bombs were being dropped over London.

A bright, cloudless Sunday in 1941 marked the beginning of Sydney’s downfall, both literally and mentally. That day forever changed his life, altering the course of his baby daughter’s life — Celia gave birth to their child in June 1941 — and many other lives that came after.

While flying over the Bay of Biscay in a twin-engine Beaufort torpedo bomber, Sydney and his three-man crew spotted a lone ship, seemingly vulnerable on the broad, empty ocean. With the reckless abandon he lived by, Sydney accelerated down into an attack. It was unsuccessful: the ship opened fire and shot down the Beaufort.

Sydney made a controlled crash. He and his crew were wounded by shrapnel but managed to ditch the blazing aircraft before it sank. Against all odds, they survived and were captured by the Germans, taken aboard the small armed merchant cruiser they had attempted to sink.

The captain of the ship was impressed by Sydney’s remarkable effort and told him, “You fly very well.”

“And you are not a bad shot,” came Sydney’s bold reply.

The sailors then beat him up for his insolence and locked the crew in a stateroom. From that moment, they became Prisoners of War, and for the next four years, Sydney was transferred from prison camp to prison camp around occupied Europe. He escaped four times but was recaptured on each occasion and punished with solitary confinement, the longest stretch lasting an excruciating six weeks.

In 1942 he was sent to Stalag Luft III in Poland, designed for troublemaking RAF prisoners like himself. It was here that he actively participated in preparations for the famous Great Escape.

From 1944 until 1945, Sydney and other prisoners were forced-marched, starving, and at the uttermost limits of their mental and physical reserves, over 400 miles through Poland and Germany as the Third Reich fell to pieces around them.

It was a time when prisoners were summarily killed by disgruntled guards just for the sake of it. Sydney once had a loaded gun pointed at his head and was told he was going to be executed. Another time, a German cook whom Sydney had befriended helped him hide while many other prisoners were shot.

Marching through a bitter winter and hostile German populations, on 16th April 1945, Sydney ended up in a village called Oerbke, near Fallingbostel, Germany. At long last, it was there he was finally liberated at the typhus-ridden, corpse-strewn Bergen Belsen concentration camp, the same place Anne Frank had died just one month prior. Sydney was shrunken, emaciated, and haunted, not unlike the concentration camp survivors.

When the war ended, Sydney was still only 25 years old. Once a tough, adventurous boy who laughed in the face of fear, he became a prisoner of his own mind and suffered flashbacks for the rest of his life. He had been shot down, wounded, captured, and held as a Prisoner of War for four years, experiencing life at its lowest.

After a long period of convalescence in England from his untreated injuries, Sydney returned to New Zealand in 1946, married another woman, and had three more children. He worked at several mining companies before becoming a mathematics teacher.

After his divorce in 1974, Sydney was diagnosed with War Shock Syndrome, now known as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Desperate for help, he voluntarily admitted himself to hospital several times and attempted suicide. In a tragic end, he succeeded in taking his own life at the age of 62.

Sydney never found the escape he sought when he left New Zealand as a teenager, nor did he ever escape the war until his final breath.

He never reunited with Celia or met his first child, Sandra.

In the days of “The Few,” my two warrior grandfathers, Bill the conformist and Sydney the rebel, were romantic heroes I would love to have known. They journeyed from the edges of the old Empire to defend Britain at her darkest but finest hour, coming together to form the greatest air force the world has known. It is with pride that I can say the RAF — and the strength, courage, and resilience of my grandfathers — are in my blood.

Afterthoughts…

Revisiting the stories of these brave men fifteen years after writing this article, originally published in The Lady, I cannot help but think their experiences of war and its devastating aftereffects laid the foundation for the trickle-down psychological and emotional damage that runs rampant through their children and grandchildren, leading to pathological family dynamics and behavioral patterns.

© Petra Khashoggi 2025

Petra this is amazing! You know more about your unknown grandfathers than I know about mine. There was a spark within you that told your childhood self you were made of warrior blood! I find it fascinating that it came to be the truth. This essay is an amazing tribute to your family, thank you for sharing it with us.

Wow. This is an enormous, wild story. It could/should be made into a movie.

It is wild to think of this in epigenetic terms, and the influence experiences of the past impact the present.