My biological father thinks my writing gene came from him, but I like to think it was inherited from my maternal grandmother. She never gave up on her dream to write, even as a struggling single mother with three jobs and no support from my grandfather, a WWII RAF bomber pilot who was captured by the Germans and held in Stalag Luft III for years, enduring life at its lowest as a Prisoner of War.

My grandmother, Celia, had another dream—to visit Paris. In 1960, she entered a writing competition with her local newspaper in Leicester. Her story won First Prize: a trip for two anywhere in the world. She chose Paris and took her teenage daughter, my mother.

While the mother and daughter duo sat in the lobby of the famed Hotel George V celebrating Celia’s win over a glass of champagne, they met a friendly man at the next table—the cousin of my mother’s future husband. A few months later, that same man introduced my mother to his cousin, and they went on to marry and have five children together.

Fast forward a couple of decades to 1980, the tail end of July. I arrived under the sun sign of Leo in the City of Angels of America’s Golden State. Cedars Sinai Medical Centre, Los Angeles, to be precise. After a lengthy naming process, my older sister decided on the first name ‘Petrina,’ followed by the middle names ‘Camille’ and ‘Celia’ (after my grandmother, who had already ascended to Heaven). The last name given to me was ‘Khashoggi’ to match my older siblings and their father. The box under ‘Father’ on my birth certificate was simply marked ‘Unknown’.

The origins of my names are Greek, French, Roman, and Turkish respectively, but I am a legit Brit—both my parents are half-British—one’s half-New Zealand, the other is half-Canadian. I did not discover the identity of my biological father until I reached adulthood, a life-changing event that happened by chance.

Throughout childhood and adolescence, my namesake, the father of my older siblings, acted as a stand-in father, though I was told to call him ‘Uncle’ to avoid confusion. Nobody knew the identity of my real father—the subject was off-limits and remained a mystery until I became friends with a girl I met in a London nightclub, whom I later discovered was my sister.

I was an international child of mystery during those formative years, traveling around the world with my mother, often left alone in the care of strangers; copious nannies like a bag of mixed nuts and a few transient men I was also told to call ‘Uncle.’

My mother moved us from the United States to the United Kingdom when I was four years old, and I had a strict English upbringing. We lived in a thatched house in Buckinghamshire, and when I wasn’t at kindergarten, I was bouncing back and forth between France, Spain, Austria, Switzerland, Kenya, and the USA.

Exposed to a lot of dramatic, unusual situations and growing up around larger-than-life personalities, I was a shy and introverted child. Leos are usually the opposite, but rather than playing with other children, I felt more comfortable in my own little dream world accessed through reading, writing, and drawing. I observed everyone and noticed everything. People intrigued me beyond words and appearances. I looked for explanations or hidden meanings as to why they did or said that, what made them use that tone of voice or facial expression, and why others responded—or reacted—in that way.

My main source of fascination was my mother. I yearned for her attention. Dressing up and looking pretty seemed to please her more than anything, and her praise and approval were of great importance. When I was five, I became obsessed with the typewriter in her home office. She let me use it to copy the words out of storybooks before I started making up my own words. I would write poems about my older siblings and give them secret names that fit their characters. My younger sister and I once made up an entire performance routine comprised of our mother’s most frequent sayings and a vast array of animated gestures that made us giggle.

Those early years were exciting, oftentimes magical. I gained such an interesting education I could never have learned at school. My older siblings’ father, the one I called ‘Uncle,’ was a loving and generous man who treated me like one of his own. He lived to have fun and made sure everyone was happy and enjoying themselves. Through my childhood lens, I vividly remember those heady, dreamlike days and wild, bacchanalian nights. In the eyes of the world, he was a legend, still reminisced about today by those who knew him. Everyone wanted to be in his orbit. Even in the presence of superstars (and there were many!), his light burned the brightest.

At the sprawling estate he once owned in Marbella, where I spent many happy summers and Christmas holidays, there was a palm tree I would often sit under to dream and write stories. I distinctly remember that tree because while sitting beneath it one day, I declared that I was going to be a writer when I grew up. A few years ago, I was invited to revisit our breathtaking family home by the new owners. Many of the rooms were still intact, and my special palm tree was still standing. We had an emotional reunion.

My family ‘situation’—and the absence of a real father—didn’t bother me or seem abnormal until I was hurled into a harsh new world at an all-girls English boarding school. The uniforms were Victorian: woolen tights, stiff collared shirts, and heavy tunics with flaps, zips, and buttons all over the place. I was so ill-equipped that I didn’t even know how to dress myself, let alone explain family dynamics.

Everyone wanted to know about my father—the man I was told to call ‘Uncle.’ Until then, I had no idea he was one of the most famous people in the world. I tried to explain to all the nosy parkers that he wasn’t my real father, but those answers bred more questions, to which I had no answers. To quell my all-consuming, inexplicable, uncontrollable feelings, I would find quiet corners around the school to sit and write my way into an alternative reality, stories that gave me comfort and the power to control what happened.

My new home—boarding school—was miserable. I was the youngest boarder, so young that all the girls in my class were picked up by their parents to go home at the end of each day. At night, we were forced to take baths in pairs, and punishments for talking after lights out were medieval.

The house (school) was old and haunted, and the matrons looked and spoke like characters that Dickens or Dahl could have made up. I was enrolled in multiple extra-curricular activities: horse riding, ballet, piano, diction, sewing… (when I think of my six-year-old self in that sewing room, I can barely believe it)… but the only thing I truly loved was writing. Mocked for bringing a ‘My Little Pony’ castle with me to school (how was I to know?) my books, pens, and notepads became my solace.

The English teacher was my earliest champion, the first to tell me I was actually good at the thing I loved. I aced every spelling test and won a silver cup for calligraphy. Words were my salvation. Years later, through the strength of my writing, I was offered a place at three of England’s top secondary schools (the equivalent of high school). Knowing I would be living with all girls again for another few years, I chose the smallest, the one I felt most at home.

At the new school, one of my first creative writing assignments was to write a ‘spinechiller’. The English teacher gave me top marks and made me read it aloud in class, to my great embarrassment. When I finished reading, I was thrilled to see a whole room of terrified faces staring back at me. I had done the assignment correctly. The teacher asked me to stay behind after class and I will never forget the earnest look in her eyes as she said, “You know that you have to do this—you absolutely must write. You have a gift.”

My mother had other ideas and signed me up with an acting agent when I was 12. I would be pulled out of school to go to London for auditions—huge parts in major movies—but as soon as the cameras started rolling, I would be dumbstruck with fright. I was much too shy and self-conscious to be an actress.

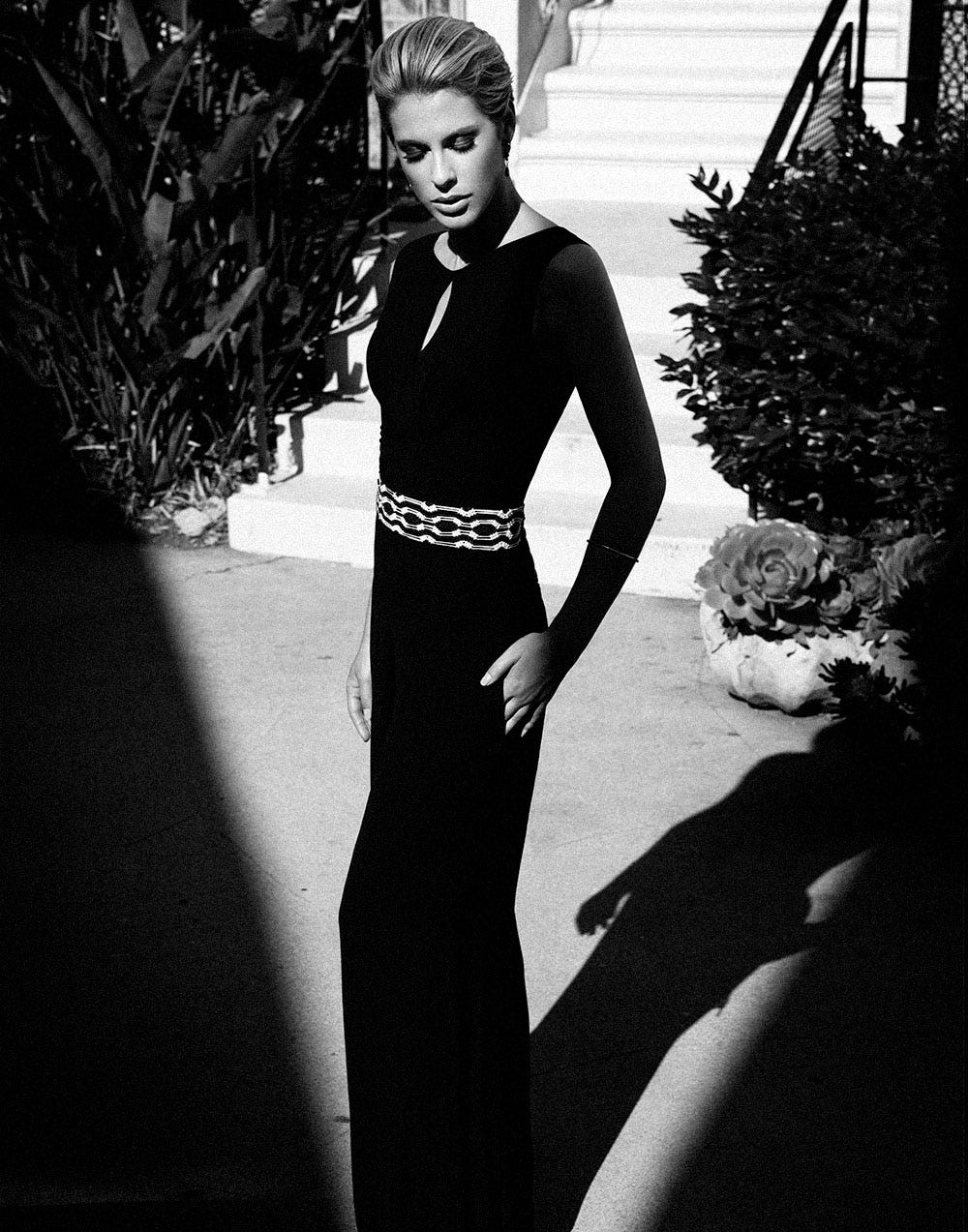

I had been programmed to believe that appearances were of utmost importance, so for a time, I ignored my dream to write and studied fashion magazines, hoping I could somehow become as glamorous and beautiful as a model (it was the 90s—the era of the supermodel.) At 16, that dream came true when I was scouted by one of London’s top model agencies. I left home and school and worked full-time to support myself, though it quickly became clear that I was not cut out for a life of ruthless scrutiny, fierce competition, and constant rejection. My confidence was non-existent, and I was a mess.

After I met my real father at 18, I was suddenly called an ‘It Girl’ and regularly featured in the British tabloids, curtailing my career as a bona fide fashion model. I had no control over what others wrote about me, and many of the stories were unkind and untrue. I couldn’t believe that journalists, mostly women who didn’t even know me, could be so nasty. I became paranoid and unable to trust people, never knowing who was selling me out. They reported on my boyfriends, my breakups, my partying, and later, my personal difficulties, splashed across the pages for strangers all around the country to read over breakfast.

I started writing my first novel—a love story between a rock star and a supermodel—when I was 19 and finished it by the time I was 21. My flatmate in London was in a relationship with a literary agent who asked if she could read it. To my utter dismay, she told me that even though it was a ‘pageturner’, my book wasn’t for her but to get in touch if I wrote anything else in the future. I stuffed the manuscript into a box and shoved it to the back of a shelf, never to show anyone again.

While I was writing that novel, a few of my articles for magazines and newspapers were published, but I never had any control over headlines, and they were always determined to portray me in ways that did not feel true. One was about my experience of getting to know my new father while he was in prison. The headline read: ‘My Heart Belongs to Daddy.’

Er, no, it did not, nor would I ever call him ‘Daddy.’

Incidentally, shortly after my father was released from prison, he reduced me to tears in public. An established writer himself, he took me out for lunch, and while I sat across from him in a crowded restaurant, he told me I would never make it as a writer. With a cold, deadpan expression and cruel timbre, he said I had the talent but not the discipline, and I should move on to find something else. We barely knew each other, but I had longed for a father my whole life, so his words were crushing and lodged themselves in my mind. He encouraged me to get a job as a secretary, or as a dishwasher in the kitchen of a restaurant. He wasn’t joking.

I was hardly making any money from modeling, and nobody in my family supported me financially, so occasionally, I agreed to do photoshoots and interviews for celebrity magazines and newspapers. Everyone was intrigued by my story, but the headlines always made me cringe. ‘Poor Little Rich Girl!’ one called me. ‘Playgirl of the Western World,’ read another. Who is this person? It was all so ridiculous.

Once, I pitched a detailed and specific article idea to the editor of Tatler magazine, a publication I had been featured in and written for many times. He did not reply, and a couple of months later, I opened the magazine to see my exact idea across several pages, the byline credited to one of their staff writers.

Around my mid-twenties, I was hired at one of the most prestigious art galleries in the world. Quite literally overnight, I became a high-powered art dealer simply because my boyfriend at the time was a collector. My new position invited more press (on top of an enormous amount of pressure), and I was being written about in American Vogue as an elite member of the European jet set.

Money was pouring into my bank account at last, I was constantly traveling (often in private jets and helicopters), in the company of royals and A-list celebrities, attending the most exclusive parties in spectacular private homes and yachts. I’m sure that all sounds fabulous and enviable, but money, fame, glitz, and glamour did nothing to fill the void within, and it pained me that I wasn’t following my dream.

At the age of 28, I quit my job (even though my boss refused to accept my resignation as he wanted me to run his new gallery in Qatar, which would have made me a kajillionaire), embarked on a spiritual path, and wrote a feature-length screenplay, a comedy about British social class.

A writer friend sent my script to an esteemed university professor, who offered me a place on his course to study for a Masters in Screenwriting and Film Production. I was the only student without a Bachelor’s degree—the professor had offered me my place on the basis of my talent. Graduating (with Merit!) was one of my proudest moments.

Meanwhile, I was still being presented with various opportunities through London PR agencies, television production companies, and publicists, which included several reality TV shows for tempting amounts of money. I said no to everything, determined to stay on course.

At the age of 31, I broke off a relationship with a man who wanted to marry me, left England, and moved to America permanently to pursue my writing career. I spent the first Christmas of my exciting new chapter with my older sister, who had just started an independent publishing company. She gave me a chance to write a children’s book and paid for an illustrator along with all the publishing costs. The agreement was that once she recouped the money, I would earn royalties from sales. I was overjoyed and so grateful—to see my first book in print was my dream come true. I dedicated it to her youngest son, my beloved nephew.

Three months after moving to the States, life threw me an unexpected curveball, ripping open an old wound from a horrific incident when I was 15. My mother had put me in a terrible situation that derailed my young life and damaged me in ways I could never have imagined. The repercussions were coming back to haunt me all these years later.

We are all vulnerable to grievous harm by other humans, but the deepest wounds are always inflicted by the ones we love the most.

I took a job at a dog hotel in New York (I wanted to be anonymous and do something mindless—it was perfect), and did Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way course. This helped me to start writing a memoir about my childhood. A friend introduced me to a powerful London-based literary agent who told me I should fictionalize the story and write it as a novel so I would be taken more seriously.

When my children’s book came out, I sent a copy to my father in London. For the first time ever—and I know he was being genuine by his voice—he told me he was proud of me and that I was an excellent writer. He said the book was so brilliant that it needed a wider audience, and he would introduce me to his contact at Bloomsbury (the publisher of Harry Potter). I told him my sister was my publisher, so he suggested that she partner with Bloomsbury in a joint deal, and then everyone would benefit. I couldn’t believe my ears!

I emailed my sister the news, but she was livid and saw my request as a huge betrayal. Her scathing email back stopped me from accepting my father’s offer, and I took it no further. After that, my relationship with my sister became fraught, and a few years later, we were estranged. Despite many attempts on my part, my sister has not spoken to me for seven years, even in a professional capacity as my publisher, so I have no idea how the book is doing or how many copies it has sold. I still have a few on my bookshelf that I keep as souvenirs.

In 2015, while I was living in Los Angeles, I wrote and produced a short film, directed by a friend and starring two actors who have since become well-known. The film was based on a true story and very low budget—everyone worked for free. I decided to play the role of the girl, which was easy because I was playing myself. It was accepted into several international film festivals and won a ‘Best Romantic Comedy’ award at the New York Film & TV Festival.

My novel took five years to write. Admittedly, I was inconsistent and sometimes did not work on it for months at a time. The story ended with that awful incident when I was 15, which was devastating to relive and write about. I did not find it healing or cathartic and I wanted to give up many times, but my literary agent was my cheerleader throughout, assuring me that she would not let any publisher reject it, and all my work would pay off in the end. She described the book as “Shakespearean,” “a blockbuster” and “a triumph.”

In 2018, every area of my life fell to pieces at once, and I descended into a severe, suicidal depression. Among the many things going on, my literary agent stopped communicating with me. My requests for updates and feedback from editors were left unanswered, and it wasn’t until I reached out to her over six months after the submission process that she finally responded to tell me lots of people loved my writing but weren’t grabbed enough by the story—and that was it. To this day, I don’t know who read it or what they said. As with my first novel, I never showed it to anyone else.

After that harrowing experience, I stopped writing anything beyond my journal. I resurfaced from hiding in 2021 when I wrote a loving tribute to my father for a national British newspaper while he was on his deathbed, thinking he may not even live to read it. Not only did he read it, he defied all odds and made a miraculous recovery. When we spoke a few days later, he said my article had touched his heart, the only time I’ve heard vulnerability in his voice. Whenever someone tells me that my words have made them feel something, I take it as a great compliment, so to hear this from him was a gift.

That article motivated me to write more about personal subjects, finally reclaiming my own narrative. Two were published in The Times and another in Perspective magazine. I started a newsletter here on Substack at the beginning of 2024, originally called ‘Beauty Chest’, now ‘Kittenesque.’

I often think of the end of Pretty Woman, that classic Cinderella story. A chipper guy crosses the street and says the final lines of the movie: “Welcome to Hollywood! What’s your dream? Everybody comes here; this is Hollywood, Land of Dreams. Some dreams come true, some don’t, but keep on dreamin’...”

Before I started writing, I dreamed, and come what may, I will keep on dreamin’ til kingdom come. My dream has changed shape and taken a few beatings along the road of reality, but it has never diminished or died.

I truly believe that those who dream hard enough will prevail, so here’s to all the dreamers. Never give up.

Your voice reads crystal clear and the power of your story becomes evident with every word.

Love what you do, and do what you love my angel xxx