British teeth, au naturel—unstraightened, unwhitened, uncapped—are suddenly all the rage.

As we snooze towards the finale of The White Lotus this weekend (although Sam “that ship has sailed” Rockwell’s character did make me laugh out loud in the latest episode), one of the biggest talking points of sleepy Season 3 has been Aimee Lou Wood’s teeth. The pretty Brit finds the fuss hilarious and says that looking natural (as in not having Botox or veneers) “feels a bit rebellious.”

Every time Chelsea (Wood’s character) and her charming teeth appear on screen, I think about when my teeth were like that. It wasn’t until my first term at boarding school, aged six that I became painfully aware of them. I had only just lost my baby teeth (and I still believed in the Tooth Fairy and Santa Claus), so my adult ones hadn’t fully come through, but once they started, they didn’t stop.

An eruption of enamel overcrowded my mouth, and my still-growing face couldn’t keep up. I was conscious that whenever I spoke, laughed, or opened my mouth to eat, all anyone could see were my teeth. They were completely out of proportion with the rest of my features and my first real insecurity.

I already had many inexplicable, uncontrollable things that made me stand out from everyone else, so the last thing I needed was for my teeth to stick out too, but there they were, as conspicuous as my last name. I quickly found ways of hiding them by pursing my lips together when I smiled and covering my mouth with my hand when I laughed, which I still do now by reflex.

That early insecurity snowballed into self-loathing, as snickering mean girls imitated me and tossed around names like “Goofy,” “Bugs Bunny,” and “Horse Face.” The last one was particularly upsetting, as I happened to adore horses and went riding twice a week, a welcome break from hellish school life.

Despite the cruel comparison, whenever I was in my own little world on a horse, I felt a comforting connection. Horses made me feel like myself again (as opposed to feeling like a freak.) They were as familiar to me as family, or perhaps they were a replacement for my scarcely seen real family.

I am aware of how mixed up that sounds. My early boarding school years sprung a lifetime of issues.

Around the age of 10, I spent a summer in California at the home of a wonderful American family with children my age. Before I returned to England, their kind mother took me to see a Beverly Hills orthodontist to address my teeth issue, and I walked out of there with a mouth full of metal and multicolored rubber bands. The rings on my back molars had little hooks to attach removable headgear. My jaw was extremely misaligned, so I was told the medieval-looking torture contraption would create space. Later, wires would be added to the metal chunks they had glued to my front teeth.

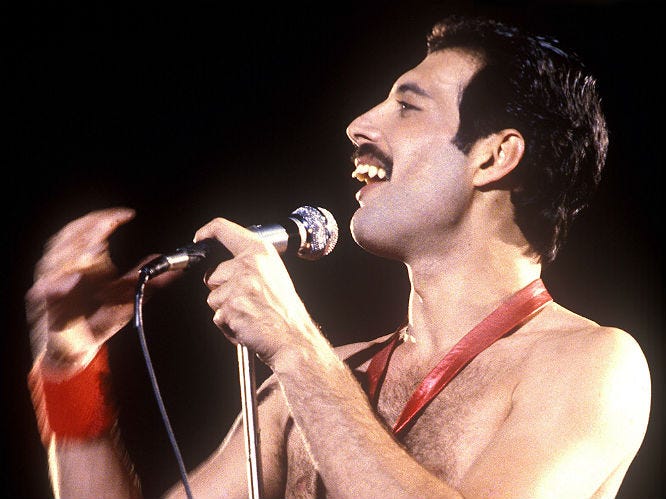

As you can imagine, when I got back to boarding school, my new headgear only made the mean girls stare, point, laugh, and call me “Metalmouth.” The solution had caused a bigger problem. I expressed my despair to my mother, who loved my overbite because she said it reminded her of Freddie Mercury’s. She was besotted with Freddie, so perhaps my teeth made her imagine me as his love child.

In my early teens, I dreamed of becoming a model, the pinnacle of physical beauty (my brains were woefully disregarded), but I didn’t think that would be possible until I got my teeth fixed. They were still very crooked and protruding, so I begged my mother to take me to an orthodontist to complete the treatment that was started in Beverly Hills, but she did not.

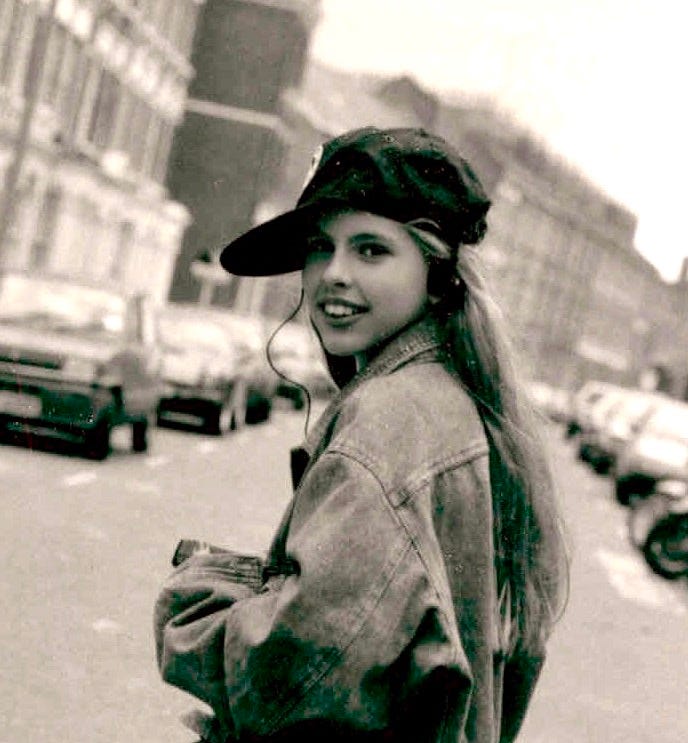

To my amazement, a model agent scouted me in a café when I was sixteen, crying mid-argument with my mother, who amongst many other injustices, still wouldn’t take me to get my teeth fixed. A surreal moment.

At the beginning of my career, I absolutely believed that I was not model material. Every time I did a photoshoot, I hated my teeth so much I would clench my jaw and hide them, discomfort showing all over my face. “Relax your mouth!” photographers would always shout. On the rare occasion I was asked to smile with teeth, I would cringe at the photos and see nothing beyond shameful imperfection.

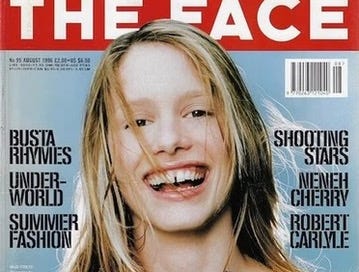

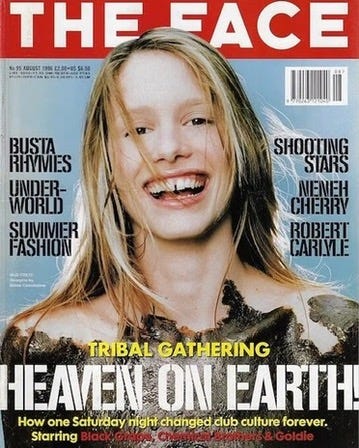

There was another model at the same agency as me who was a couple of years older. Her defining feature was her unconventional, gap-toothed smile. She was refreshingly real, and I was in awe of her confidence. The fashion world loved her, and she graced one of the coolest magazine covers, those magnificent teeth on full display:

I finally made enough money to get mine fixed when I was in my early 20s, which involved having teeth removed to create more space, followed by retainers and then Invisalign. I would have preferred not to spend so much time and money on my teeth, but my quest for perfection was insatiable.

When I turned 40, I gave up wearing my nighttime Invisalign. As a result, my teeth have now moved. I’ve never had them professionally whitened, crowned, or bonded, nor do I plan on getting veneers (the bad ones look blindingly fake, and the good ones cost a house). Three of my four top incisors are in disarray. One of my front two teeth has a small chip, the other one is discolored (one dentist described that tooth as “traumatized”), and my right lateral incisor twists at a 45-degree angle. But of course, nobody notices these changes but me. My mind likes to play tricks on me and harp on the strings of childhood pain.

My smile is huge, amplified by an exaggerated dimple. All that suffering was not for nothing; I get more compliments on my smile than anything else. The last words Milica Kastner, one of my late great friends who lost her battle with terminal cancer in 2021, said to me were: “Only Julia Roberts has a smile like yours.”

My teeth are far from perfect, and at this point, I don’t want them to be. I used to be so judgmental, rejecting that frightened girl at boarding school who tried everything to hide and fix that glaring flaw. Now, when I see photos of my much younger self, I feel so much compassion for how hard I was on that girl.

If I could go back and say one thing to her now, it would be this: perfect is not beautiful, and beautiful is not perfect.

Am so late to this tooth fairy tale, but I adore your sweet little-kid smile! My youngest daughter probably endured the same Beverly Hills orthodontist if only because I thought I was helping... Her teeth are beautiful now--no bonding required, but the pain she must have endured. Oy. As a parent, all you wish you could do is go back in time and absorb any of that suffering your child might have felt and return it to her as love. 💛

Thank you for pointing out how we go from one extreme to another. In this case, the “Hollywood smile” of straight white chiclets perfectly aligned has returned to “looking natural” where crooked protruding teeth are now the rage. I’m for a happy medium like your last photo.